Dordogne is a gorgeous, cathartic trip down memory lane

By Phil Bothun

In the early part of the pandemic—somewhere between sourdough and Tiger King—I got deep into family genealogy. I’d pour over digitized documents, building out a family tree I’d never really learned.

A bit later, I excitedly shared some of my finds with my grandfather, asking him if he remembered any of the people I found and showing him a French marriage record from 1635. I asked him about his great grandfather, Phillistin, and his eyes (well, eye singular) lit up as if no one had ever asked him. In that moment, I was starkly reminded just how human my idealized grandfather is.

That’s the magic trick of Dordogne: humanizing the people and places we only remember from childhood. There are moments of pain and anger, loss and remembrance, all tucked nicely into a tale about the most idyllic summer holiday for a 13 year old in rural France.

The most striking thing about Dordogne is the art. Everything is a pastoral watercolor, beautifully rendering your grandmother’s cottage, the local surrounds, and a riverside village. It’s an absolutely breathtaking style choice that works so well in stillness and motion.

The palette is somber in the modern day, muddy browns and rusty reds as you arrive at a home that feels in mourning. As you’d expect, the childhood memories is where the art style really sings. Every screen is a gorgeous pastoral paintings filled with rich color and life.

You play as Mimi, a 30-something young woman traveling to her recently deceased grandmother Nora’s home, seeking a box Nora left her. Throughout the game, you’ll explore the country home by interacting with objects by twisting and turning them to pull off a pen cap, sizzle a pan of frying potatoes side to side, or solve simple puzzles. The interactions are all quaint, but they’re tactile and evocative, harkening back to flashbulb memories you may have from your childhood.

Something happened to Mimi 20 years ago during the summer she stayed with Nora, but she can’t remember. You’re here now to reclaim your memories of that fateful summer trip as much as to say goodbye to Nora. As you explore the home, you interact with objects that warp you back to 13 year old Mimi’s summer holiday, slowly moving through the summer to unravel your memory.

As current day Mimi attempts to find this box Nora left for her, she finds objects that flash her back to being 13: a pen, a kayak, a binder, and more. Each memory is painted wonderfully, but the pastorals and the stories within aren’t saccharine.

Through collectible letters and tapes, it’s revealed that the relationship between Nora and Fabrice, Mimi’s father, is tense, usually resulting in shouting matches. Nora is a complex woman, living alone after her husband Edouard recently passed. She is independent, clever, and compassionate, but still grieving.

As you navigate the world, you can take photos, record audio, discover stickers, and find floating words. You’ll come across an expansive view of the valley with a large, selectable “Beautiful” floating on the horizon, or the words “Bitter” and “Sad” are plastered on a cereal box. Some of these words are choices and others are simply emotions you can feel.

At the end of each day, you’ll compile your sounds, stickers, photos, and adjectives into a scrapbook reminder of your time. The words you pick up are cues for a poem in your scrapbook: select a word and choose one of three poem phrases. Put three poem phrases together for day’s poem. You start to see the complexity of Mimi’s emotions here; the day you spent planting in the garden started with being sad because you missed your friends. And your poem can reflect that. You can give into the melancholy and write about loneliness and darkness, or make a poem reveling in your newfound green thumb.

In an early chapter, Nora emerges from a locked room in the attic to answer the phone below. Mimi attempts to enter, but Nora nonchalantly dissuades her, telling her it’s nothing interesting. When you next take control of modern day Mimi, you enter the attic room, slowly revealing a model railroad village reaching wall to wall, swirled chalk drawings covering the floors.

Beneath a drawbridge for the train is a stack of cassette tapes featuring Edouard and Nora talking about Edouard’s remission and later descent into illness again. Stepping into this sacred space recontextualizes Nora and her actions. Did you need to get a trowel from Edouard’s tool shed because Nora wanted your help or because it pained her to enter his space?

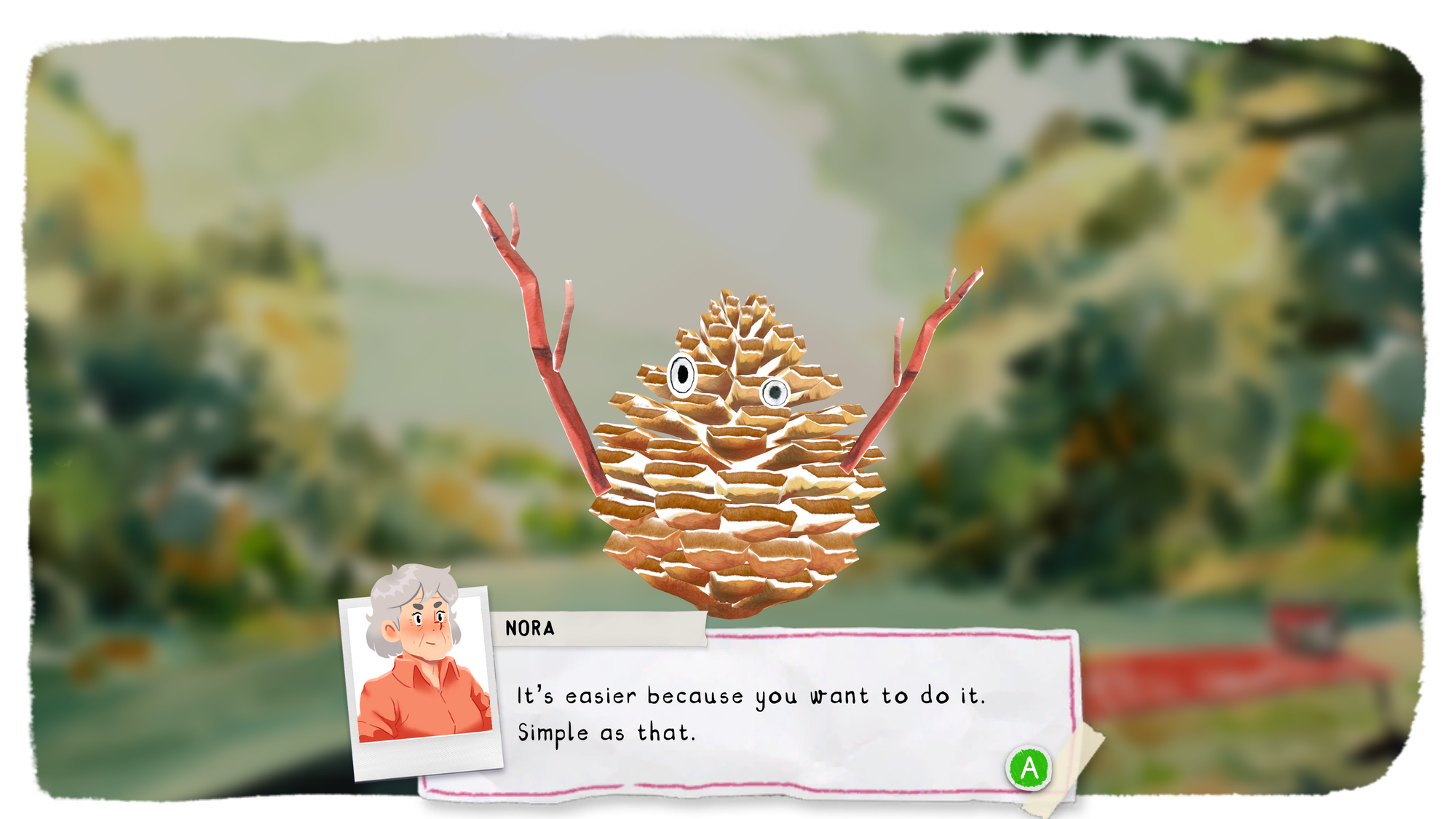

In the penultimate chapter young Mimi asks Nora if you can invite your friend, a young boy known as a thief around town, to have a picnic. You fry potatoes and garlic in duck fat, then pack them up and head for beach, rowing your newly repaired kayak down the Dordogne. You set the picnic out and, waiting for the boy to arrive, Nora asks if you’d like to make some decorations. After you glue some goodly eyes and sticks to a pine cone, Mimi mentions how the project was easier than expected. Nora responds, “It’s easier because you wanted to do it. Simple as that.”

So much of Dordogne’s gameplay is making soft choices. How will you reflect on the day? Do you linger on the darkness or find light in moments that brought fear? Do you stop and record the sounds of a babbling brook or take photos of soaring hot air balloons? When presented with the unexpected—a lost loved one, a vacation far from your friends, a quest when you least expect it–do you rage at it, bitter at the loss of what could have been?

Dordogne’s storytelling revolving around grief, anger, and misunderstanding, pain that festers for more than 20 years. But, just as Nora said, recovery becomes easier simply because this time you wanted it.