INDIKA is a devastating game about the Devil on your shoulder.

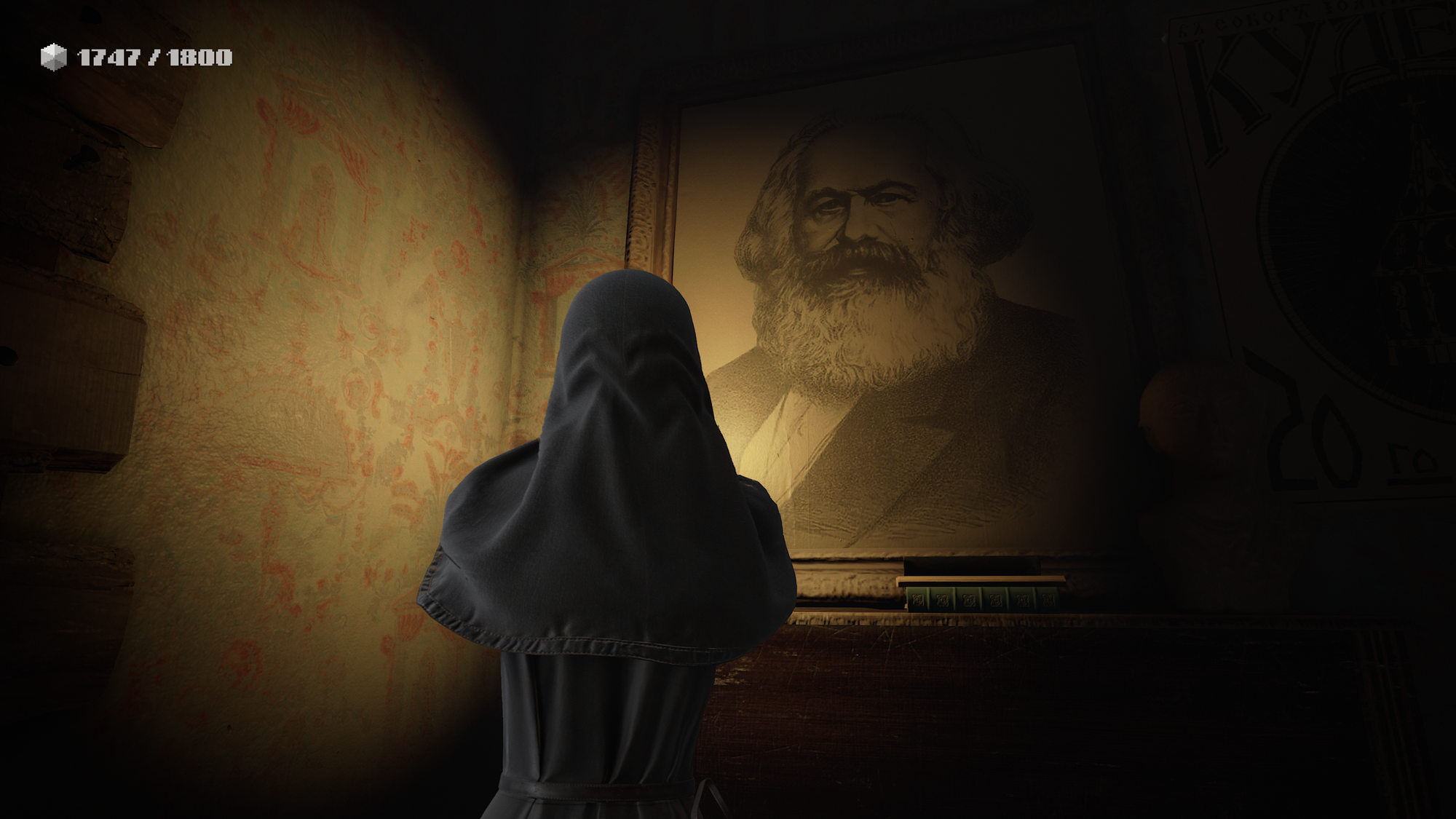

Indika, the titular nun of Odd Meter’s sophomore game, is having trouble fitting in at her late-nineteenth century Russian Orthodox convent. She’s trying her best to be pious like the other nuns, but there’s just one problem: the literal Devil. Or so the game wants you to believe.

You play through INDIKA as a young nun sent on a mission to deliver a message outside the convent walls. You’ll solve simple puzzles, light prayer shrines, explore a surreal interpretation of late-nineteenth century Russia, and pray…as a puzzle mechanic. It’s hard to explain what INDIKA really is: part third person puzzle game, part walking simulator, part pixel art platformer, and so many other things. There’s even a Pacman level. Perhaps the best thing to be said about INDIKA is that it’s very good.

Odd Meter, a small development team formerly based out of Russia, pulls no punches in their logical dismantling of organized religion, specifically the Russian Orthodox Church. The world of INDIKA is bleak, filled with barren towns, grim, senseless death, and disgusting authority figures. This game is not for the faint of heart with content warnings including implied sexual violence and grievous bodily harm. INDIKA isn’t lurid in its depictions though, each moment of horror serving the game’s themes.

For all the darkness though, the environments of INDIKA are gorgeous. Homes in the countryside are rendered in incredible detail, the density and care rivaling The Last of Us: Part II. The more surreal elements of the world design—towering, twisted buildings, villages built on cliffs held together with tethers, and a fish canning facility packed with car-sized tins of fish—imbue the game with a haunted feeling more akin to Little Nightmares than your typical walking simulator. You always feel small, like the world is leering at you, judging you.

The game opens with Indika being given a letter to deliver in a far-off city. You leave the convent walls for the first time in over a year, then make your way to the train station, solving a few simple puzzles along the way. You’re not alone though. Following you through every twisted hallway is your inner monologue, sowing self-doubt, interjecting lewd intrusive thoughts, or goading you to act on your basest instincts. The Devil on your shoulder, if you will.

During several intense moments, Indika is overcome by this voice, bathing the screen in an intense red light and literally pulling the world apart around you. The voice, uninhibited, rants at her to challenge her beliefs. Your only recourse is to hold L2 to pray, shutting out the voice and slamming the world back together to traverse a particular platforming challenge.

During her travels, Indika meets Ilya, an escaped convict with a twisted, gangrenous arm on his way to Spasov, his hometown and the current location of the Kudets. The Kudets is a holy relic believed to possess miraculous powers of healing. Ilya explains that God has spoken to him and is guiding him to Spasov where his arm will be healed. Indika chooses to help Ilya travel to Spasov instead of completing her assignment in hopes that the miracle of the Kudets can fix her mind and remove this doubting voice.

INDIKA wears its message on its sleeve at times, whether it’s lovingly crafted cutscenes between Indika and Ilya, or through walk-and-talk segments that feel like Philosophy 101 courses. The game has a clear anti-religion angle, but somehow manages to walk the fine line of criticism without devolving into an antagonistic Reddit Atheist. Rarely is the game subtle about its views—at one point a character suggests a serial child murderer be canonized for saving the souls of children before they could sin—but I always felt that it served the message without being overbearing.

All of that third person walking and talking sounds rather similar to most a story-based indie games you’d play. Where INDIKA shines is its use of out-of-place video game mechanics to further its message. As you make your way across the landscape, you’ll find prayer shrines or religious artifacts rewarding you with points. These points are spent in a very simple skill tree, increasing your guilt, shame, or grief. Like I said, it’s not a subtle game.

There are long flashback segments that detail Indika’s life before the convent, rendered as 2D pixel art platforming, a topdown racing game, or rhythm platformer, and a Pac-Man clone. Each of these sections serve as a reprieve from the hyper-realistic drudgery of modern day Indika, depicting a story of young love. I felt a looming sense of dread as the flashbacks ticked closer to the start of the game and I wasn’t disappointed. You’ll hear some of the best music the game has to offer in these segments: poppy electronic beats more in-line with whimsical indie platformers or a particular lo-fi music channel. It all comes together so nicely.

My gripes with INDIKA are tiny, for such a small development team, I continued to be floored by how well crafted every part of INDIKA is. At times, Indika’s line reads can feel blown out and I had to look up a particularly tricky puzzle solution, but I’m just nitpicking at this point.

INDIKA is consistently unnerving, depressing, and surprising from beginning to end. The team nails the ending too, doing one of my favorite tropes: letting you keep playing the game until you get it. INDIKA is rich with beautifully haunting visuals and deep, ponderous explorations of faith. It’s rarely a fun game, instead you’ll leave after five or six hours, most likely feeling empty.

I suppose that’s the goal; after all, the points really don’t matter.